The 'primitive preferences and beliefs' explanation is strongly linked to the behavioural research I blogged about previously, implying that bubbles emerge as a result of human psychological tendencies (particularly herding). Stein, however, focuses primarily on the overheating effect of 'institutions, agency and incentives'. He argues that bubbles in financial markets often result from agency problems: institutional investors disguising low-probability risks in an effort to 'reach for yield'. The systematic understating of the risk involved in an asset ultimately leads to systematic overpricing of that asset, inevitably causing a bubble.

This appears consistent with the most recent financial crisis. From 2000 onward, sub-prime mortgages and other junk bonds were repackaged by banks into derivatives specifically designed to 'fool' the algorithms of rating agencies. As a result, the price of these derivatives rose significantly beyond their true value, and this only became clear when large numbers of borrowers defaulted.

What can this tell us about how to identify a bubble in credit markets? Stein argues that a major warning sign is 'rapid growth in a new [financial] product that is not yet fully understood'. This may be the result of innovation, a change in regulations that creates new loopholes, or by a change in risk-taking incentives. It may be the case that such a product is being used by bankers to obfuscate systematic risk.

He warns that the next financial bubble could arise through 'collateral transformation', whereby the high credit standards of a clearinghouse are circumnavigated by borrowing Treasury securities from a third party using junk bonds as collateral. The result is not only that risks may be understated, but that an additional party is exposed to a potential default.

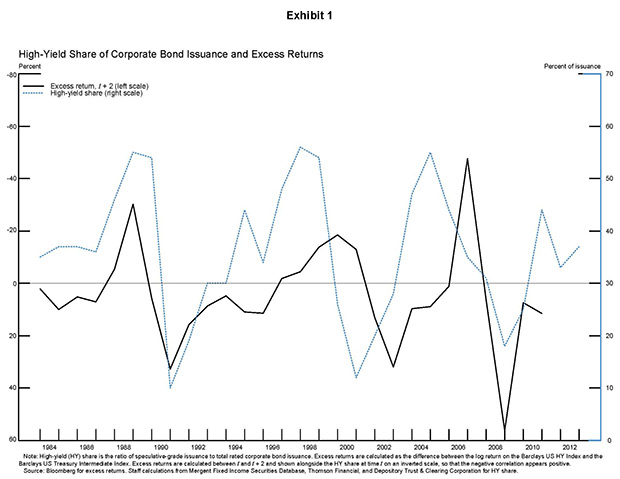

Another signal that the market may be overheated is the 'high-yield share', defined as issue by speculative-grade firms divided by total bond issue. Greenwood and Hansen (2012) graph the high-yield share against excess returns, finding a strong negative correlation:

There thus appears to be some empirical evidence for the theory that credit markets overheat as a result of agency problems.

While Stein's speech focuses on the exploitation of loopholes, Slate magazine point out that a credit-market bubble can also emerge from outright fraud, referencing a recent court case suggesting that JP Morgan illegally misrepresented the value of mortgage-backed securities to ratings agencies. A bubble might be compared to a naturally-occurring Ponzi scheme, but sometimes it may not be as 'naturally-occurring' as it first appears.

Another interesting aspect of Stein's explanation is that it links the emergence of a bubble to the emergence of new technology: in this case, new financial instruments. As Pastor and Veronesi (2005) point out, this seems to be a recurring theme in the history of bubbles, and the link will be examined more closely in future posts.

References:

Greenwood , Robin, and Samuel G. Hanson, "Issuer Quality and Corporate Bond Returns" unpublished paper, Harvard University (2012), retrieved from: http://www.people.hbs.edu/Shanson/Issuer_Quality_20120905_FINAL.pdf

O'Hara, Maureen, 'Bubbles: Some Perspectives (And Loose Talk) from History', The Review of Financial Studies 21 (2008), pp. 11-17

Pastor, Lubos, and Pietro Veronesi. Technological revolutions and stock prices. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working paper No. w11876 (2005).

Stein, Jeremy C., 'Overheating in Credit Markets: Origins, Measurement and Policy Responses' (2013), retrieved from: http://federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/stein20130207a.htm#fn14

Yglesias, Matthew, 'Reading Fraud out of the Institutional Perspective', Slate (2013), retrieved from: http://www.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2013/02/07/jeffrey_stein_on_credit_institutions_don_t_forget_the_fraud.html

No comments:

Post a Comment